Achieving supply-chain predictability works out to be a competitive advantage for most manufacturers. Each year, business planning models are filled with assumptions about a manufacturing network’s capability to produce and ship product as promised to the customer base. These assumptions often are conservative and based on a history of less-than-optimum performance.

Manufacturers need to understand their current capabilities and continually improve their uptime and process availability. Traditionally, the capabilities of these facilities in their networks vary as a result of product mix, processing, packaging capabilities, shipping issues, access to markets, distribution networks, and the availability of their assets. However, many uptime issues are caused by the unavailability of their assets (unreliability); these problems result from equipment failures and process and operational issues. Manufacturers strive to improve reliability to have predictable supply-chain processes that deliver product to customers on time and meeting all “purchased” specifications.

Some manufacturers take a strategic approach to improving their manufacturing network (site) availability by instituting and implementing corporate reliability guidance. This isn’t the common approach, however. Many manufacturers let their sites develop their own practices; these may not reflect industry best practices and may compete with (and lose to) other corporate initiatives. Don’t let this happen at your organization – here’s a five-step process to developing a corporate reliability initiative.

Pre-Planning: why develop a reliability program?

The value proposition for a corporate reliability program can cover many aspects important to the business.

The evaluation begins with analysis of what is plaguing the business followed by an assessment of future needs that will be met with this comprehensive equipment-care initiative. The value proposition’s development starts with company and business leadership as they begin to understand the potential case for improving asset care.

Reducing the impact of environmental, health, and safety incidents caused by equipment failures leads our value proposition list. Also consider that unplanned events can result in customers not getting their orders on time.

Gaining manufacturing network capacity by improving plant uptime can defer capital investment and can also be an objective of a corporate reliability program. Gaining a fraction of uptime from several facilities can negate the need to build new facilities, saving millions in capital investment.

Other parts of the value proposition are:

- Focusing the organization on business goals and objectives

- Gaining a more-predictable supply chain

- Reducing overall operating costs by reducing breakdowns

Overview of the 5-step process

Certainly, all of these factors lead to improving bottom-line results from sales revenue improvement, higher margins, and lower operating costs.

The process begins with senior company and business leaders developing the business case they will use to “sell” the corporate reliability strategy to the organization. This assumes a fairly enlightened leadership that understands the potential benefit for the application of maintenance and reliability practices.

The process also likely will involve some role shuffling. Certain roles will need to have responsibilities added to their portfolio; other personnel may need to be promoted to roles such as global reliability leader. New hires may be necessary, too. Laying the foundation for success in this initiative also demands thoughtful development of vision and values.

Before any work gets started, metrics are needed to gauge long-term progress. These are high-level lagging metrics to be reviewed by leadership quarter to quarter. The corporation also needs to know where each site will be starting from in implementing the initiative. An internal or third-party assessment will dictate what each site will focus on to reach the targets of the high-level metrics.

Ensuring the organization has the knowledge, competencies, and skills to properly deploy the corporate reliability program is the next step in this process. Every aspect from hiring, job descriptions, job promotion, incentives, and training needs to be reviewed and adjusted. Training must be customized for each organizational level. Leadership will need training on reliability, machine failure, and establishing the business case for reliability investments, while floor-level personnel must learn troubleshooting and root-cause analysis skills.

Developing the reliability program involves establishing the playbook by standardizing and writing out the methods and tools each site will use in this initiative. The playbook can be organized by several means as body-of-knowledge pillars, work processes, and selected tools and methods. Failure reporting is also started to accelerate the remediation of bad actors across the network. A useful strategy is “loose and tight,” which allows for both corporate guidance and site flexibility to use site-developed methods.

The last step in this overview of the corporate reliability strategy development process is implementing the initiatives across the network through sharing results and leveraging the network to “pollinate” all sites in best practices. These efforts should be supported by regular reporting of metrics and company meetings to assess progress, share results, and celebrate achievement of targets.

Step 1: Develop the business case

Guidance for improvement of reliability exists in many forms. Companies can do nothing and allow sites to develop “pockets of excellence,” but these efforts succumb to people changing roles and momentum can be lost. Senior leaders can provide verbal support during visits, but their advice can be ignored after they leave. Unfortunately, this can also lead to confusion resulting from various interpretations of what was heard. More-effective guidance will come through a structured program built upon a strong business case.

The business case should focus on remediating what has plagued the business in the past and what the future focus should be in response to market conditions. The business case can focus on these issues:

- Uptime

- Operating cost

- Supply chain

- Demand

- Deferring capital

- Safety

- Product cost

- Breakdowns

Typically, the business case for a corporate reliability program must be “sold” at the highest level in the company, given that top-down support is its lifeline. If the board decides that certain goals must be delivered in a timeframe that cannot be supported by current industry experience, someone needs to apply the brakes. No matter how long it takes, waiting for the endorsement of leadership is vital.

Step 2: Leadership structure

The effectiveness of corporate reliability programs varies depending on:

- Leadership – who drives the initiative both from a corporate and business position

- Strategy – targeting what the business needs to survive

- Structure – including the “right” elements

- Culture – collaborating, focusing on defect elimination, and being proactive

- Talent – supporting its implementation

- Level of buy-in from participants – accepting the initiative from the boardroom to the production floor

- Competency – obtaining knowledge of practices

All of these factors are important through this journey to achieving the business-case targets. Hiring the leadership to take it forward is next.

Before developing the reliability strategy, certain other elements are needed: values, beliefs, and policy. Values for reliability might be “Achieve 95% uptime across all our production processes,” “All personnel will focus on elimination of failure,” or “We will work to eliminate all risks to our stakeholders from unplanned events.” Values should come from the senior leaders of the company and be included in the reliability program. Participants must believe in what can improved reliability can deliver and what it means to their businesses.

Next to be developed are the company’s beliefs. Reliability beliefs set the target for the culture. An example of a set of beliefs is:

- Equipment failures are preventable

- Reliability is everyone’s business

- We use the right tools

- We report all equipment issues

- We investigate abnormal conditions and failures

- We have visible metrics

- Management is committed to reliability

- Reliability issues are resolved

- Reliability is for the entire lifecycle

- We use and follow instructions

The reliability policy should provide the business case for reliable equipment and the manufacturing process. It should include guidelines for maintenance and reliability, focus areas for improvement, a set of measures, and a time horizon in which to see the effort’s benefits.

For instance, a policy could open with, “Our production processes will operate without failure and will enable the extension of turnarounds to industry benchmarks.” Added to this expectation is, “We will focus our efforts on our largest-volume production lines, measuring our progress through asset utilization and mechanical availability targets with an expectation that in two years we will achieve 95% overall asset utilization and 85% mechanical availability.” The policy can include objectives around recording downtime and other practices to be implemented. The policy should provide the “what” but not the “how” to be effective.

Metrics are as important as the guidance itself. Initiatives that get measured get improved. Luckily, maintenance and reliability (like baseball) are full of statistics. However, the trick is to develop the right mix of leading and lagging metric dashboards that will inform senior management as to progress. They will connect with those on the production floor as to how they can “move the needle.”

A few metrics should be used at a corporate level. They should be well-defined and their reporting be standardized so all sites collect them in the same way. These could include:

- Example 1: Operating asset utilization and $ maint / RAV

- Example 2: MTBF and downtime

- Example 3: MTBF, downtime, and deviations (failures, upsets, nonconformances)

Finally, for this step, each site should know its starting place. An internal or third-party assessment should be performed across the network to determine the implementation level of maintenance and reliability practices for each site.

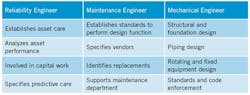

Step 3: Competency and baselines

Organizations need to have individuals with the right competencies to carry out a corporate reliability program. This starts with hiring people with the right skill and knowledge sets. Job descriptions need to be modified for use in the hiring process. Table 1 shows the distinction between reliability engineers and others involved in asset care.

In addition, certification should be specified as a prerequisite. Certifications like the Certified Maintenance and Reliability Professional (CMRP) designation should be an expectation for reliability engineers.

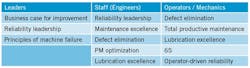

For those already in the organization, raising competency can be achieved through training from either in-house staff or third-party organizations. The curriculum should vary based on where someone is in the organization. Table 2 offers an example of topics that could be offered to various team members, based on their roles and responsibilities.

Step 4: Program structure considerations

Following the “loose and tight” strategy, it is best to specify principles and high-level practice expectations and leave the rest to the sites to decide how to implement these practices.

For instance, it is acceptable to specify that downtime needs to be understood and analyzed and projects be developed to eliminate it but not to collect the information or specify who should do it. This description for a critical-equipment list specifies details of the practice to be implemented but leaves some space for sites to customize their approach.

Principle: Critical-equipment list

Critical equipment is equipment that merits more maintenance time and resources because of its value to the business. Identifying critical equipment within a production facility ensures that equipment receives the right priority level when determining allocation of resources. Critical equipment should be addressed before noncritical equipment is. (Note: The critical equipment list is not intended to fulfill any regulatory requirements, nor does it preclude or replace any HAZOP, MAPP, or other safety studies.)

Practice

- All equipment within the production facility (including rotating and fixed equipment, structures, systems and other components (electrical, mechanical, instrumentation) has been evaluated and processed through the critical equipment evaluation

- The critical-equipment list is available and is used in establishing priorities for preventive maintenance activities, condition monitoring activities, and spare-parts inventory decisions

- The critical-equipment list is used to prioritize maintenance tasks

- Failure of a piece of critical equipment triggers a detailed assessment of the failure, such as an RCA or RCM

If you’re too prescriptive, you run the risk of overburdening sites that must make judgments on how far to implement a maintenance and reliability practice based on their size, resource levels, and business mission. It is best to provide the minimum level of practice and have each site decide what course of action is appropriate for its situation. As an example, larger sites with more resources can handle the expectations of a defect elimination process, while smaller facilities might only perform root cause for failures that cause more than a day of downtime. Failure to right-size the initiative can result in “unfunded mandates,” leading to the collapse of any attempt at implementation.

Finally, sharing knowledge of failures and fixes accelerates improvement. Fully utilizing the failure-code functionality of the CMMS for all sites is the first task. The triggers should establish which failures are tracked to root cause (e.g. >day down, >$50,000, large EHS incident). A standard root-cause tool across the network should be used to share root-cause findings and actions to remediate similar situations at other sites.

Step 5: Business and site implementation

Metrics are vital to determining progress. As mentioned earlier, only a few metrics are needed from a corporate perspective. Each site should use about 5-10 metrics that tie directly to the corporate metrics. Each network should be responsible for metrics that represent their activity; these can then be leveraged across all sites (Table 3).

Recognition is the “grease” that keeps the initiative moving forward. Multiple types of recognition are needed from the corporate level to the site level. For instance, at the corporate level, sites that achieve their corporate reliability targets should be publicized, and corporate should sponsor internal networking meetings. At the business level, corporate could sponsor CMRP certifications, recognize leaders throughout the organization who produce uptime and cost results, and offer incentives for achieving reliability goals.

So what separates good programs from those that do not help the individual manufacturing site? At the top of the list is leadership, starting with the CEO and the board of directors. Whether the program is driven “top-down” or “bottom-up” will have a lot to do with its success. Bottom-up initiatives have a small probability of success. Top-down initiatives get more attention, structure, funding, and scrutiny. The scrutiny cascades across the entire organization, and each business unit then deploys it according to its needs. This deployment leads to the next important criterion, structure.

The right structure is vital to effective deployment. It should be based on a “loose and tight” protocol. Diving too deep into prescribing practices and methods will not allow site to develop “areas of excellence.” The “tight” structure should include company values along with a reliability policy. Some prescriptive high-level guidance is acceptable – for example, requesting that downtime be recorded or that sites have a bad-actor list. It should be modeled after operating excellence standards outlined by organizations like the Society of Maintenance and Reliability Professionals (SMRP) or other third-party subject-matter experts.

Participant buy-in is a must. An effective deployment hinges upon individuals at the various sites becoming part of a network that focuses either on the entire initiative or one segment, such as operator care, planning and scheduling, or defect elimination. This is where the “loose” part of the deployment strategy is best leveraged. Those who feel ownership can take the initiative further than any senior leader sitting in the corporate headquarters can.

Other factors that can doom a corporate reliability program are focusing on cost, not having the right talent in place to lead and deploy the program, creating “one-size-fits-all” plants with requirements for best-practice implementation, not recognizing that a minimum of two years is needed to see improvement, and forgetting to include the operations and engineering groups as partners with maintenance in the program’s deployment.

Conclusions

Based on the criteria, structure, leadership, culture, talent, and level of buy-in, a corporate reliability program can drive the achievement of corporate and business goals. Want a more-predictable supply chain? Work on building – and honing – your corporate reliability strategy.