How would you like to add 57 persons for free to your existing 100-person workforce to do extra proactive work? You can, by understanding how much of an impact planning and scheduling proactive maintenance can have for your plant.

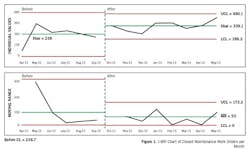

A picture (or chart) is worth a thousand words, so take a look at this: Figure 1 shows a maintenance group at a grain plant making a dramatic increase in work-order completions. In a single month, the plant improved from completing only 238 work orders per month to 339 work orders per month, a 42% increase.

Considering that plants usually complete most of their reactive maintenance, all 101 extra work orders completed are, by definition, proactive. So planning and scheduling answers the question, “How can we complete more proactive work to head off reactive work when we have our hands already full with reactive work?”

Nevertheless, planning and scheduling programs frustrate most plants, and they do not achieve the great benefitfrom what should be a rewarding endeavor for maintenance. Most plants think that by providing great job plans, jobs will go smoother and the maintenance group will complete more (and better-quality) work. They also think that by providing great schedules, they will have better coordination between operations and maintenance so that the maintenance group will complete more work. Finally, most plants let urgent work go directly to the maintenance group and bypass planning to quicken the maintenance response. This thinking won't suffice to implement successful planning and scheduling programs.

Success depends on recognizing and addressing subtle issues in both planning and scheduling. To achieve the dramatic productivity increase possible through planning and scheduling, management must first understand why there is an opportunity. Then, management must understand and actively manage three precepts for proper planning and scheduling. First, planning should provide for ever-improving job plans. Second, scheduling should provide 100% loaded schedules as weekly goals. Third, planners should try to plan urgent work if the crews will not start it immediately.

The opportunity of planning and scheduling

To begin, consider why an opportunity exists for productivity improvement and the benefit such an improvement could provide. While it is hard to believe, productivity measurements of maintenance craftspersons at good plants shows so-called wrench time at only about 35%. This means that of the available labor for the day – the amount of time that persons are actually moving jobs ahead and aren't in nonproductive activities such as getting parts or tools, traveling about the plant, being in meetings, or being on break – is only about 3.5 hours out of a 10-hour shift.

This seemingly low rate is universal because humans feel “busy” at about 35%, and over the years plants adjust their labor capacity to “take care of operations” and keep everyone busy.

Nevertheless, in a matter of weeks, a proper planning and scheduling system can boost wrench time to about 55%. This is a 57% improvement. (The grain plant in Figure 1 achieved 50% wrench time in its 42% productivity improvement.)

Furthermore, suppose a plant had 30 maintenance persons; under these conditions, a 57% improvement in productivity would be the equivalent of adding an extra 17 persons for free to do extra proactive work. While some estimates are as high as $100/hr, consider $50/hr as a fully loaded rate for a craftsperson. The annual salary value of 17 persons would be nearly $1.77 million. Now consider the industry “1:10” rule of thumb, whichis that every $1 spent on extra proactive maintenance saves $10 on the bottom line (largely from improving plant availability and reliability). The extra $1.77 million opportunity yields $18 million in profit per year for the plant by using the extra free labor to do proactive maintenance.

Precept 1: Provide ever-improving job plans

The problem with implementing planning is that management usually oversells planning. Management tells craftspersons that they will get perfect job plans and never have to hunt for parts anymore. Of course, that is an impossible task. Many jobs run into unexpected situations, but because management promised perfect plans, these craftspersons insist that planners help find the extra parts or information needed. Consequently, planners usually become so involved in helping jobs in progress that they do not plan all the new work. Then they help even more jobs in progress because many jobs have no plans. Soon they do little advance planning at all.

Instead, plants should implement planning as a Deming Cycle in which planners give craftspersons a head start but largely position themselves as craft historians who collect feedback to improve job plans over the years. Figure 2 shows how planning uses Dr. W. Edwards Deming’s Plan-Do-Check-Act cycle. A single planner cannot be as smart as the cumulative wisdom and experience of 20–30 craftspersons, and so the craft-historian approach allows plants to implement planning to institutionalize knowledge.

This proper approach requires plants to address special issues to support the planning program. The plant must protect planners from being taken away from planning duties, and planners themselves can't afford to help jobs in progress to the extent that they do not plan all the new work. Planners also must create files or computer job plans tied to equipment asset numbers to keep track of feedback they receive.

Planners also cannot become bogged down in making perfect time estimates. Frequently, planners can make a good-enough guess about the time needed for a job to allow for supervisor control. As far as the job-plan detail level, it is more important for planners to plan all of the work than to plan only, say, four jobs out of 10 but in more-precise detail. These last issues are controversial, but consider that although the plant wants a great time estimate and a great initial plan, if planners are not planning most of the work, they are not running a Deming Cycle, and they are not improving as many plans over time as they could.

The final issue with planning is that planners must plan enough work so that the plant can schedule enough work.

Precept 2: Treat scheduling as goal-setting

There are different maintenance schedules. Generally, the yearly schedule is about budget and money; the monthly schedule is about keeping up with preventive maintenance; and the daily schedule is about which individuals will do which jobs and about coordinating times with operations for clearance.

The weekly schedule affects workforce productivity. Most plants mistakenly think of the weekly schedule as five daily schedules created before the week begins. These overly precise weekly schedules usually frustrate plants because daily maintenance is so dynamic. In the real world, many jobs run over or under their time estimates, and operations frequently interrupts the maintenance forces.

Because daily maintenance has so much churn, most craft supervisors develop a keen eye toward taking care of operations and keeping everyone busy. Unfortunately, while such plants can have good reliability, the workforce still has only 35% wrench time. Instead, plants that each week simply start maintenance crews with a goal of work matching their available labor capacity quickly achieve 50% to 55% productivity levels.

This amazing improvement opportunity exists because of Parkinson’s Law, which states, “The amount of work assigned will expand to fill the time available.” The application to maintenance is that because everyone is “busy” at 35% wrench time, plants do not assign enough work.

Dr. Peter F. Drucker explains in his management-by-objective (MBO) philosophy how critical it is that one understands an activity's purpose. The purpose of scheduling is to complete more work – not, as most plants think, to complete the schedule. This mistaken notion becomes counterproductive when these plants give crews only the amount of work that they normally accomplish to achieve high schedule compliance. These plants stay at 35% wrench time.

Instead, consider the framework of a proper scheduling program. The proper planning program has planned enough work so the plant can schedule more work than normal. The plant has a credible priority system. The scheduler (usually the planner) uses the priority system and other considerations to load up each crew with enough work to fill 100% of its available labor hours for the next week as a goal. The scheduler creates a list or bucket of work without specifying days. Finally, management expects schedule compliance of somewhere between 40% and 90%.

The result is that a fully loaded crew completes more work with lower schedule compliance than a lesser loaded crew that is mandated to achieve higher schedule compliance. The first crew has achieved the plant’s objective, which is to complete more work than normal. That extra work is usually proactive work, precious to the plant bottom line of profit. Note that the bucket of work is both more effective and easier to create than a detailed weekly schedule.

Inherent in the 100% work goal concept is that management allow supervisors to break the schedule when appropriate. This notion is similar to management not insisting that planners must produce “perfect” job plans.

Precept 3: Plan reactive work

Most plants bypass planning with urgent work. Beyond “all hands on deck” emergencies, many plants have a significant amount of urgent work that should not wait until next week. Yet not all of that work must be started this morning or even this afternoon. Therefore, because proper planning does not have to produce “perfect” plans, planners can quickly plan some urgent work.

To plan urgent work, planners should first check with supervisors. For any urgent work that the supervisor has not already started (or is about to start), the planners should try to look quickly at the job and the history or plan file to see if they can develop a quick plan. Often, a previous plan might exist that will help a craftsperson avoid a previous issue. Hence, planners can run the Deming Cycle for some urgent jobs while never telling supervisors to wait. (Furthermore, some of the quickly planned jobs also end up not being started that week and can then be candidates for next week’s schedule.) In this manner, planners can properly provide great help for urgent work.

Conclusion

Planning and scheduling programs frustrate many plants that do not understand the subtle issues. Trying to make perfect plans and schedules usually causes most of the grief. Instead, management should allow planners to improve imperfect plans gradually over time to provide for the best job-plan development. Simply starting maintenance crews with a full bucket of work each week as a goal can produce a dramatic productivity increase, but only if management allows supervisors to break the schedule. In addition, because planners do not have to be perfect, they can plan some reactive work quickly, which further helps craftspersons improve plans and supports weekly schedules.

Our three essentials for successful planning and scheduling, then, are as follows:ever-improving job plans, fully loaded schedules, and quick planning of some reactive work. These precepts are not natural and so must be thoroughly understood and actively managed.

References:

Deming, W. Edwards (1986). Out of the crisis. Cambridge, Mass. Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Drucker, Peter F. (1954). The practice of management. New York, NY. Harper Collins Publishers, Inc.

Parkinson, Cyril (November 19th, 1955), Parkinson’s law, The Economist as reported in http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parkinson's_law accessed 10 Oct, 2013.

[sidebar id="4"]