Last month, Part 1 addressed the relationship between weight and volume of air, explained how to reduce ambient conditions to standard conditions and explored the performance differences between compressor types.

Another potential rule of dumb says that every 1 psig increase in pressure changes the input power by 0.5%.

|

View more content on PlantServices.com |

Therefore, the thinking goes, “If I reduce the pressure by 10 psig at the compressor discharge, I’ll get a 5% decrease in the input power required.” There are some limitations you might not be aware of.

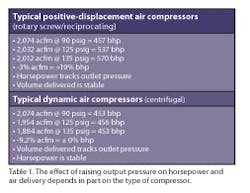

This only applies to positive-displacement units, not dynamic units (Table 1). The net effect on a centrifugal discharge pressure change (not including any unloading controls) is machine-specific and you must refer to its performance curve. However, on many commercial units at higher pressures, the flow (scfm) drops and at lower pressure the flow increases; usually at the same or a similar input power. This effect generally covers a relatively narrow operating band.

This only applies to 100-psig-class equipment. One client called us to say his compressor service representative had told him this 0.5% rule applied to his 300-hp Bellis & Morcom unit, which was running at 535 psig. The service rep suggested dropping the pressure to 435 psig because the plant was using the air at 380 psig. This 100-psig drop would offer a 50% power reduction by virtue of the 0.5% rule. Our client thought that a 150-hp reduction seemed too good to be true, and wanted our opinion.

Our answer had two parts. The first was to always reduce the pressure to the lowest effective value that allows optimum productivity and quality. This saves power, as well as wear and tear on the equipment.

The second was that the suggested reduction was too good to be true. We gave our client some measured field data from similar units. But the statement that lit the cranial light bulb was, “Why not reduce the pressure by 400 psig, get a 200% savings, get your compressed air free, and sell the other 100% (300 hp) back to the power company?” “That’s not possible,” he replied. That’s exactly the point.

Guidelines are fine for ballpark estimating when you understand the technology fully, but otherwise they can lead you down the path to making your own rules of dumb. Check the facts when making critical decisions.

Storage and demand

The final guideline originally hatched as a rule of dumb. It has never been correct under any circumstances, yet it has been written about repeatedly, advertised and appears in instruction and training manuals and the Internet. That rule says a two-step capacity control compressor (load/no load) requires 1 gal. of storage per acfm of air delivered if it’s to operate correctly and efficiently.

A two-step or load/no load control also is called full on/full off. It’s a constant-speed capacity control (the motor continues to run) that matches the compressed air supply to the demand. When it senses the cut-in or load pressure, the compressor goes to full flow and stays there until the system reaches cut-out or unload pressure. Then, the inlet valve closes, cutting off flow to the system. The compressor doesn’t reload until system pressure falls to the cut-in or load pressure. The normal operating band usually is 10 psig.

In operation, this control must handle changes in demand while avoiding short-cycling, which is loading and unloading occurring rapidly as the system pressure rises and falls. Short-cycling is hard on the operating components – motor, bearings, drive and cooler – and leads directly to premature failures. Short-cycling on lubricant-cooled rotary compressors often won’t allow the compressor to reach full bleed-down and idle. Such units never reach the lowest possible no-load input kW, which has a negative effect on efficiency. A minimum effective storage controls this phenomenon.

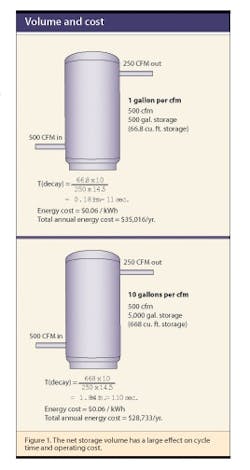

Fifty percent load on a two-step control produces the shortest cycle. Figure 1 shows a 500-cu.-ft. compressor using the 1-gal.-per-cubic-foot rule of dumb and its calculated cycle time – 11 seconds loaded, 11 seconds unloaded, repeating ad infinitum. In the second image it shows the same compressor but with 5,000 gal. of storage (10 gal./cu. ft.) and its calculated cycle time of 110 seconds (1.8 minutes) loaded and then 110 seconds unloaded. In this case, proper storage saved a client more than $6,000 per year (20%).

One gal. of storage capacity per cfm delivered isn’t enough effective storage for two-step control units. At 14.5 psia, it takes approximately an additional 2,800 acfm to pressurize a 400-cu.-ft. receiver from 0 psig to 100 psig. At 11 psia inlet pressure, it takes approximately an additional 3,600 acfm.

Short-cycling is costly. For example, not giving the lubricant-cooled rotary compressor with a 40-second bleed down sufficient time to get to full idle imposes a cost of more than $6,000 per year.

Defining effective storage

When it comes to establishing and using effective storage, most plant professionals avoid mechanical problems by keeping cycle times greater than 1 minute load/1 minute unload. This calls for an effective storage of between 4 gal./acfm and 5 gal./acfm. Be sure you have enough bleed-down time to reach full idle. Check the unit in question. Bleed down time could range from 7 sec. to more than 3 min., depending on size, brand and model. Older units normally have longer bleed-down times.

A final thought: Total effective storage doesn’t need to reside exclusively in the receiver. With proper system design, equipment selection and operation, header piping also can serve as effective storage.

Hank van Ormer owns Air Power USA Inc., in Pickerington, Ohio. Contact him at [email protected] and (740) 862-4112.

Figures: Air Power USA