As a recent CMRP, I have been immersed lately in all things reliability. I’ve read through the writings of Ramesh Gulati and the SMRP library, participated in webinars by Ricky Smith, and subscribed to industry magazines like Plant Services (obviously!) and Reliable Plant.

More often than not, I drive to work listening to podcasts narrated by two industry pros who helped reinforce my interest in the field, Rob Kalwarowsky and James Kovacevic. Yet somehow, despite this wealth of knowledge, reliability is an industry at once half a century old and still struggling to emerge.

Why is that the case? Why is it so hard to actually implement these ideas in practice?

In my opinion, our industry mavens are beyond reproach. What they’ve managed to create over the last few decades is a genuine service for which we should all be grateful. And based on personal experience, we can safely rule out the content and quality of the reliability body of knowledge as well. Where we hit a roadblock is in its application, which inherently requires very high administrative overhead.

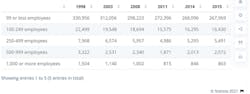

There is a major gap between theory and practice for plants that cannot staff accordingly that contributes to this failure to launch. For example, the well-accepted recommendation for planner and scheduler head counts can range anywhere from 1 per 10 or 20 tradespersons. However, roughly 90% of the factories in the U.S., about 270,000, have fewer than 100 people total (see Table 1). This includes maintenance, operations, sales – everyone.

So, for the median factory in America, best practices suggest that factory hire a formal planner/scheduler once the maintenance department reaches approximately 10% of the company’s total headcount. Hardly good advice.

Another example is failure modes effects analysis, a cornerstone of reliability best practices. An FMEA is the recommended basis for nearly every strategic initiative in maintenance and reliability, from PM development to equipment design, safety evaluations and technical staffing decisions. Proper analysis requires a heavy administrative investment, both upfront and down the road to maintain the relevance of the findings.

Without a high level of organizational discipline, the effort runs a high risk of ultimately failing. How many of the 100 total people in your median American factory are going to have the time, desire, and institutional backing to embark on such an uncertain journey?

As William Jakobyansky writes in his excellent article, “Why Maintenance Departments Regress,” the default state for a maintenance department is reactive. Evolution to higher levels of industrial existence is like pushing a boulder up a hill: hard to do and painfully unforgiving. Letting up means starting all over again, so the odds of survival are not good. IoT? Machine learning? Inventory turns and ABC storeroom analysis? How many plants ever mature to a state where these subjects are relevant?

Jakobyansky argues that smaller maintenance departments are successful (i.e., not reactive) based wholly upon the quality of their key decision makers – individuals who “get it” on their own through some combination of training and experience. This defeats the purpose of an industry group in the first place, which is to standardize the field and expand the availability of good practitioners beyond those who are naturally talented.

Often the advice from SMRP and other industry sources is to essentially truncate recommendations. If a plant lacks staffing for scheduling or planning, then don’t schedule or plan. If there is no reliability engineer, then don’t use your CMMS for anything but breakdown reporting. Without clerks, don’t kit parts or digitalize your storeroom. Such solutions deprive reliability professionals, particularly those with less experience, of much-needed tools for improvement. It’s no wonder high individual performers are the only ones able to navigate these waters.

Reliability practitioners at smaller plants, already chronically underappreciated and overworked, have few if any resources or communities to draw upon for support, both mentally and professionally. To boot, as Jakobyansky writes, “in any site-management meeting, those with maintenance experience usually are outnumbered 10-to-1 or more by those with only production experience. This means that the deck is stacked against maintenance”. Against this backdrop, the reliability body of knowledge, ostensibly meant to provide outside support for these very reasons, is full of recommendations that are practically dead on arrival.

Few resources are available to help facilities bridge the gap between theory and the real world. And as a result, reliability best practices are simply not applicable to the median-sized manufacturer. Greater discussion, development and consideration is needed to bring smaller facilities up to speed in order to advance the industry as a whole, and this is where this blog hopes to make a contribution.

About the Author

Alex Ferrari

Alex Ferrari, CMRP, is a Maintenance Manager of a specialty cosmetics manufacturer in Charlotte, NC. He has worked in the chemical and nuclear industries both in the US and abroad in Argentina. As a blogger and as a maintenance professional, Alex aims to explore the challenges faced by small and mid-sized facilities without the budget for by-the-book reliability programs.