In my last post, we established that your company is either interested in developing a reliability program or already has one in place. If you already have developed a reliability program, but have not yet achieved the results you hoped for, maybe the lack of having a reliability strategy or the method in which you planned your roll-out, have limited your success. We touched upon this topic in the 3rd and 4th bullet points of the last post. There are certain program elements such as developing a fully functional computerized maintenance management system (CMMS) which do not produce results in and of themselves, but lay the foundation on which the program’s overall success is built. These initiatives must be started early in the program for two reasons.

1. If your foundation is not functioning at best practice levels, complex activities such as root cause failure analysis (RCFA), reliability centered maintenance (RCM), and bad actor identification and resolution cannot be completed in an effective manner. As an example imagine how difficult it would be to identify bad actors if you were not fully utilizing your CMMS’s work order system or if your costs were not captured accurately at the equipment level. Foundational activities such as these should be initiated in tandem with those reliability improvement activities which produce the initial savings, create enthusiasm for the program, and fuel further investment.

2. Getting the foundational elements of your program functioning at best practice levels usually takes a huge amount of time and effort. Progress can be slow and activities such as tree structure clean-up and material creation can take years to complete if the CMMS was not setup with a best practice end in mind.

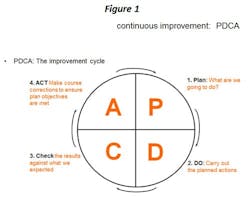

I have found that a program element has a greater chance of success if it is laid out in advance in a stepwise fashion. Our reliability strategy has 29 program elements and they are grouped as beginning, intermediate, and advanced activities. Most of the elements which make-up our program are fairly common and are considered by most as generally accepted industry practices. Success is not achieved by stumbling across some secret formula others have not tried. Results are created by the thought process, intent, and effort which go into the development of each program element. Those who succeed just work harder than most of us, there are no magic bullets. As I stated earlier, certain program elements act as precursors to others, and should be among the first you roll out. Timing and sequence are all important; getting too many initiatives started at the same time stymies culture change; rolling out program elements in the wrong order can doom the program to failure. Each program element should be developed with what I will call a Plan, Do, Check, Act or PDCA action cycle. (See Figure 1).

The PDCA action cycle is an effective method to build your program, and those organizations which thoroughly map out their strategy, usually achieve the best results. I will explain the PDCA action cycle in greater detail in the following chapters.

I cannot stress how important the “Plan” step in the PDCA action cycle is. Several questions should be considered in the “Planning” stages.

- Is the activity well-defined? What will be the scope covered under the program element?

- What resources will be required to ensure the program element can be successfully completed? Are the resources committed to the activity and do they have sufficient time to complete the activities assigned to them?

- What is the anticipated payback for the program element? Based on the resources needed to successfully complete the activity, is the payback attractive or will other initiatives produce a better return on investment?

- Do I have the buy-in of all stakeholders who will be participating in or committing resources to the element?

- What needs to be done before roll-out? Should the activity be rolled out in stages or all at once?

- How will I measure success?’

As you will see in the example I am about to use, these steps are iterative in nature and the answer you develop for one question may influence the answers of several more. To illustrate, I will use the example of RCFA. Most reliability professionals would agree that a RCFA program is an essential part of the overall reliability excellence strategy. So let’s see how answering these six questions above might ultimately determine the outcome of the roll-out.

What events will require a formal RCFA? If you want RCFA’s to be completed on only the most business critical failures, triggers should be established. But the answer to question two will influence the threshold these triggers will need to be set at. If the site has two reliability engineers who will complete the bulk of the RCFAs, and it is determined that with other priorities, they can only manage to complete three RCFAs per month combined, triggers must be set so on average, three RCFAs are generated per month. Sounds simple but how many organizations overlook resource loading when making they determine the scope of a program element? RCFAs will not be effective if evidence is not preserved at the time the failure occurs. Thus operators, mechanics, and front line supervisors must be aware of the triggers and know their role in evidence preservation. Answers such as these help define the answer to question five, as training is one of the activities which need to be done before roll-out. Equipment costs that exceed routine maintenance as well as the cost of lost production calculated for past events that met trigger threshold limits, can help define potential savings for the program. Once work scope is firmly established, all stakeholders involved can be identified and solicited for their buy-in. Some stakeholders might not be able to support the process in their areas at the time of roll-out: knowing this helps answer the question on whether the program should be rolled-out in a step-wise fashion or in all areas simultaneously. And finally, once a firm scope is established, KPIs can be developed to help measure program success. Hopefully, I have shown that starting a RCFA program without first developing a well thought out strategy, leaves many questions unanswered and can be a limiting factor for success.

Careful planning leads to better execution in the “Do’” phase and helps establish the timing for each step in the program rollout. As an example the RCFA triggers must be established, documented, and communicated to all responsible parties. Training must be completed so that operators and front line supervisors will recognize a triggered event and mechanics will save parts such as belts and bearings, preserving each item in their “as found” condition so failure analysis can be completed. Strategic planning leaves fewer things to chance and increases the probability that your program will meet its goals and objectives. When your initiatives are well planned and predicted results are achieved, you build credibility and give the perception that you are competently managing the program. The result: people will be more apt to support your initiatives in the future and your program will flourish.

The KPIs you develop in the “Planning” phase act as the “Check” step in the action cycle. I like to establish what I call results based and behavioral based KPIs for each program element. Results based KPIs measure program payback while behavior based KPIs measure program planning and execution effectiveness and stakeholder buy-in. While the second set of metrics is somewhat soft, both are equally important measures of success. In our example, establishing a RCFA program, the obvious results based KPI might be future cost and production loss avoidance by completion of the action items or findings developed from the RCFA. We had one fairly critical fan on a spray drying system where five bearing failures occurred in a two year period. After completion of several action items, the fan went four years without another bearing failure and that failure was caught early enough on the PF curve so that collateral damage was avoided and production loss was held to a minimum. While results based KPIs are essential to communicate program success, behavior based KPIs can also be established and used to determine whether the actionable steps completed in the “Do” or execution phase of the PDCA action cycle were effective. A behavior based KPI might be the measurement of the number of triggered events where the evidence was preserved and the initial investigation was completed by the front line supervisor. A high % of compliance indicates the stakeholders know their role, have bought into the program, and are fulfilling their assigned duties. Remember, some of the events will occur in the middle of the night on a Saturday evening, while the reliability engineer who will eventually be assigned the RCFA when he or she comes in on Monday, is sleeping. If the evidence ends up in the scrap dumpster and the crime scene is cleaned up before the investigation starts, the chances of finding the root-cause are greatly diminished.

The final phase in the PDCA action cycle is the “Act” step. This is the step where you monitor the program roll-out and determine whether all of the executable steps have been completed, the initial goals have been reached, and the calculated payback has been met. Any course corrections necessary to get your program element back on track can be made at this time. An illustration of how the “Act“ step might be used in our RCFA program roll-out could be if the number of triggered events exceeded the available hours that the reliability engineers assigned to the program had available to facilitate the analyses. An act step might be to assign a third reliability engineer to the program if one exists or to raise the trigger threshold of events to reduce the number of RCFAs generated. Either way, the “Act” step can be used to develop a continuous improvement loop, forcing a whole new series of Plan, Do, Check, Act steps.

The Plan, Do, Check, Act action cycle is but one method used to develop a strategic focus for your reliability excellence program. I am interested in hearing what others are doing to increase the likelihood of their program roll-out’s success. As you read this post ask yourselves a couple of questions.

1. Do I have stated goals and objectives for each program element of my reliability program?

2. Have I spent time considering which steps are necessary to achieve my stated goals and objectives?

In my next post we will look at CMMS implementation and its importance in building a firm foundation on which to build your reliability program. May your equipment run reliably and may your weekends be filled with time spent with family and friends rather than on emergency calls. See you down the road to reliability at mile marker number 43.