Industrial cybersecurity is all over the news, and not in a good way. Our most vital industries – including power, water, nuclear, oil and gas, chemical, food and beverage, and critical manufacturing – are under attack. The gravity of the situation became clear when the FBI and the Department of Homeland Security went public in October about existing, persistent threats. Virtually or not, bad actors are among us.

Unlike physical attacks, cyberattacks are nonstop. Cyber hackers have graduated from simple mischief and denial-of-service attacks to ransomware, theft of competitive information, interception or altering of communications, the shutdown of industrial processes, and even knowledge manipulation through the news and social networks (it’s bigger than just politics). Who knows what’s next?

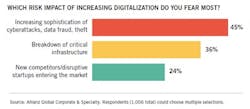

Digitalization and connectivity are heightening cyber risk, though they are foundational to the Internet of Things (IoT), cloud computing, Big Data analytics, and artificial intelligence. Breaching a single connected operational technology (OT) device or system puts everything on the network at risk.

Low-security and small networks provide easy access for bad actors, whether they’re traditional hackers, black-hat hackers making money on the dark web, nation-states, or malicious insiders. Human error and negligence also are cyber risks.

To establish and sustain cybersecurity and restore the confidence of the public, greater awareness of threats and ownership of risks are imperative. In addition to mastering basic security measures, industry needs to detect and respond to attacks with persistence and resilience. Trust is not a strategy.

Fortunately, industrial software, technology, equipment, and service providers are fast ramping up their defenses, and dozens of new cybersecurity technology and services firms are offering to help. Consultants, legislators, regulators, and standards bodies also have prominent roles, but it is the end users, ultimately, who must put the cybersecurity puzzle together.

Here, several industry and cyber professionals weigh in about industrial producers’ cybersecurity risks and responsibilities and offer their actionable recommendations.

How bad is the problem?

When companies are surveyed about their top business risk, the answer increasingly is cybersecurity, says Alan Berman, president and CEO of the not-for-profit Disaster Recovery International Foundation (DRIF). The IoT – now a $3 trillion to $6 trillion industry – is opening new doors to cyber hackers. An estimated 50 billion connected devices (handhelds, sensors, etc.) are in use already.

Speaking at the Society of Maintenance and Reliability Professionals (SMRP) 2017 Conference, Berman noted that cyber hacking has matured to become a sophisticated industry seeking to penetrate devices and systems through the weakest link in the chain, with the goal of profitability. “It is a business and we have to deal with it as a business,” he explains.

The weakest link could be a vending machine in the plant, Berman says. “Once hackers get on the network, they can get into everything,” he says. “When that happens, it could be months before the breach is discovered. What looks like a malfunction could actually be a hack.”

Until there’s awareness within the maintenance organization of the security risks associated with adding or replacing a connected device, the number of cyberattacks an organization sees will continue to rise, says Howard Penrose, president of MotorDoc.

Penrose has easily uncovered industrial cybersecurity gaps using Shodan.io, a search engine for finding internet-connected devices. In one case, “We found numerous points of access to different IoT devices using (the organization’s) default passwords, including links to the documents with those passwords,” he says. “In another case, an OEM had installed software on wind generation systems that allowed them to be turned on or off with a smartphone app.”

Most people equate cybersecurity to the network or IT, but the things that go “boom” in the night are on the industrial control system (ICS) side, says Joe Weiss, managing partner at Applied Control Solutions. “Not enough people are looking at this,” he says.

Weiss has been compiling a nonpublic ICS cyber-incident database that he says already contains more than 1,000 actual incidents, representing about $50 billion in direct costs. Each new entry serves as a learning aid or reminder; often they’re logged in his cybersecurity blog.

“People worry about the IT/OT divide, but the real divide is what comes before and after the Ethernet packet,” suggests Weiss. “Before the packet is where the Level 0,1 devices live (sensors, actuators, drives), and that’s where cybersecurity and authentication are lacking.”

As managing director of ISA99, Weiss recently helped start a new working group for Industrial Automation and Control System Security standards to address the cybersecurity of Level 0,1 devices.

Sheila Kennedy, CMRP, is a professional freelance writer specializing in industrial and technical topics. She established Additive Communications in 2003 to serve software, technology, and service providers in industries such as manufacturing and utilities, and became a contributing editor and Technology Toolbox columnist for Plant Services in 2004. Prior to Additive Communications, she had 11 years of experience implementing industrial information systems. Kennedy earned her B.S. at Purdue University and her MBA at the University of Phoenix. She can be reached at [email protected].

Fear or fight?

Digitalization adds significant value despite the cyber risk. “Don’t fear connectivity – the benefits are too great,” says Eddie Habibi, founder and CEO of PAS Global. On the other hand, he cautions, the threat of cyberattack is imminent and proven; critical systems are vulnerable; and “every minute, day, or month that you put off securing your systems, they remain at risk.”

Malicious code can sit dormant on a network for months or years before it suddenly activates, explains Habibi. The consequences can be significant to safety, production, the company’s reputation, insurance costs, and even the cost of borrowing for organizations that are not considered secure. “It’s beyond the theft of data; it’s now hitting the bottom line,” he adds.

While OT operators face all of the cybersecurity risks common in IT environments, many of the tools used to mitigate those risks are not available for OT networks, observes Chris Grove, director of industrial security at Indegy. He notes the following crucial distinctions:

- OT networks are not designed from the ground up with security in mind, meaning that industrial controllers are not typically protected with authentication, encryption, authorization, or other standard security mechanisms.

- A successful cyberattack on an OT network could have safety, financial, and environmental implications.

- It is much more difficult to monitor OT networks than it is to monitor IT networks because of the lack of monitoring tools, the proprietary protocols in use, and network isolation.

With the right tools, such as those developed for OT asset discovery and for tracking of user activity and changes to operational code, operators can identify risky configurations, malware, human errors, and insider attacks.

“Security is not a static thing,” cautions Dr. Allan Friedman, director of cybersecurity initiatives at National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) in the U.S. Commerce Department. “It needs to be adaptive, resilient, and scalable.” He continues: “For example, don’t assume that an air-gapped system (unplugged from any network infrastructure) will stay that way. Improperly trained personnel may establish new connections, or the USB drive used for a software update may carry an infection.”

A simple ICS internet search revealed a small business wind generator with no cybersecurity in place.

Security by design and necessity

Trust is the new currency; more regulations are coming; and cybersecurity is not an option because we are moving toward digital at the speed of light: Dr. Ilya Kabanov, global director of application security and compliance for Schneider Electric, made these three points at the ASIS 2017 international security conference.

Kabanov urges OEMs to embed privacy and security in the products themselves. “It is not security vs. innovation; security requires innovation,” he explains.

Richard Witucki, cybersecurity solutions architect at Schneider Electric, agrees. “Since security by obscurity is no longer a viable option, it is incumbent upon manufacturers such as Schneider Electric to embed cybersecurity directly into their products,” he says. “By doing this, we enable the end users to take a much more defense-in-depth approach.”

The digital world must bridge the gap between innovation, security, and privacy.

Schneider Electric’s approach includes actively training its development teams and engineers in secure development life-cycle programs, incorporating established security controls into its products, and conducting exhaustive internal and external testing. The ISA99/IEC 62443 set of standards was chosen because it addresses cybersecurity at several levels, including the products, the systems, and the development life cycle of the products and solutions.

“We all rely on products that control our critical infrastructure to perform as expected,” Witucki says. “Ironically, because these systems are so reliable (e.g., PLCs controlling a seldom-used diesel generator for 20 years), they have now become a vulnerability within the shifting threat landscape.”

Predictive maintenance (PdM) system and service providers are also tackling cybersecurity. Paul Berberian, condition monitoring specialist at GTI Predictive Technology, has heard customer comments ranging from “It is not an issue” and “Nothing in the plant is connected to the outside world,” to concerns about internal secrets being vulnerable through an internet connection.

“Maintenance and reliability departments want to use PdM technology, but some don’t want to fight the battle internally with IT,” explains Berberian. “In my opinion, the concern for most of these companies is that hackers will be able to find a way into their plant network through the PdM data portal.”

To mitigate this risk, GTI uses SSL certificates to ensure the security of its sites; it requires encrypted user names and passwords for access; it encrypts the stored data; and it uses a secure (HTTPS) web address.

Operational security technology partnerships are also forming. “Manufacturers and utilities want a single, accountable provider with a reputation like Siemens’ rather than a dozen suppliers,” says PAS Global’s Habibi.

The Siemens-PAS partnership looks to help companies that are struggling to establish adequate cybersecurity regimens. The PAS Cyber Integrity analytic detection engine identifies and tracks cyber assets, enabling fleetwide, real-time monitoring of control systems. Forensic and analytics technologists at the Siemens Cyber Security Operations Center apply their expertise to this information so they can dig deeper and provide a more-robust response to potential threats.

“There is a 100% probability that any company will suffer from a cyberattack, and these attacks travel with lightning speed – how resilient will your response be?” asks Leo Simonovich, vice president and global head of industrial cyber security at Siemens.

What should you do right now?

First, master the basics: access controls, backup and recovery, software updates and patching, network segmentation, system hardening, and malware prevention on end points. Consider using a search engine like Shodan.io to quickly gauge risk exposure.

Cybersecurity should be treated like lean manufacturing and Six Sigma initiatives; it should be a continuous process reviewed and assessed on a regular basis, says Schneider Electric’s Witucki. “It is not a goal, but a journey,” he says.

He suggests selecting a cybersecurity standard appropriate to your industry and organization, and then focusing attention where it is needed most with a gap analysis or risk assessment. This starts with an inventory of all computer-based assets (hardware, software, etc.). “When you consider some of this equipment may have been operating for 20 years inside an enclosure, you start to understand why this may be difficult,” adds Witucki.

GTI’s Berberian’s urges both industrial solution providers and end users to establish a strategy and security protocol that suppliers must meet. “A strategy that everyone understands, other than ‘We will never use the cloud,’ is most helpful,” he says.

To secure complete operating environments, companies must begin by addressing the fundamentals: discovery, prioritization, monitoring, and protection of their assets, advises Siemens’ Simonovich. He also advocates that company leaders consider addressing OT cybersecurity as one of their core responsibilities. This requires ownership, a strategy that looks at the challenge holistically, and strategic partnerships with best-of-breed companies.

NTIA’s Friedman suggests the following when acquiring new equipment or devices:

- Ask questions regarding security: What are the risks, and how can they be mitigated?

- Employ basic security hygiene: Use strong passwords and security credentials; apply patches promptly; employ network segmentation; and “know what’s under the hood” (e.g., which operating system is used).

- Partner with other sectors and organizations on design principles: Your problems probably aren’t unique, and others may have developed useful security solutions.

Ensure that the default passwords are changed, especially in the settings of variable-frequency drives, energy monitoring devices, and other connected systems, adds MotorDoc’s Penrose. Also, never let a vendor bypass security to connect to the network. “We once found that a USB WiFi card had been installed on a secure network so a vendor could access the system remotely, eliminating the isolation of the critical systems network,” he says. He adds that if the IT personnel are capable, they should be performing device vulnerability analyses.

Indegy’s Grove says that while active, passive, and hybrid ICS security monitoring approaches all have advantages, a hybrid approach is likely to provide the best value for most organizations because it “gives organizations total visibility into their OT network and environment.”

Applied Control Solutions’ Weiss reminds us that it isn’t always clear what is or isn’t a cyber event, and SCADA is not a fail-safe to identify potential cyberattacks. By design, in some cases it may not detect critical malfunctions. Weiss suggests getting involved in the new ISA99 working group and sharing your ICS cyber incidents with him ([email protected]).

Finally, and perhaps of most importance, cautions Schneider Electric’s Kabanov, everyone from executives to end users must decide whether cyber protections make sense. If they don’t believe they do, they’ll work around them.

Much more needs to be done to protect the critical industrial sector. The bad actors already are planning their next move. What’s yours?