Uncovering the missing pieces: 4 case studies in building reliability programs

Building a reliability program can be like trying to put together a puzzle without the help of the picture on the box. You see all the pieces in front of you but without a good idea of what the bigger picture looks like, the difficulty level increases dramatically.

Four maintenance teams from very different industries found themselves in this situation, moving toward an improved reliability culture yet slowed down by unforeseen gaps in their approach. This article showcases four case studies that were presented at the 2024 Leading Reliability Conference, and illustrates how each team found the right missing pieces with the help of a trusted partner that put them in place to drive reliability success.

Making the juice worth the squeeze

Four years ago the maintenance team at E. & J. Gallo Winery discovered that business as usual was resulting in unacceptable cost over-runs. “We were spending millions of dollars and not knowing where we spent it,” said John Lazar, the winery’s director of engineering and maintenance, adding that one location had overspent their maintenance budget by a couple of million dollars. “When management asked, where did that go? How did we spend it? No true answer.”

To get those answers and better control costs Lazar was asked to implement a world-class maintenance (WCM) program, focusing on five Gallo facilities to better understand what those teams were doing well and which pieces of the reliability process were missing. “Do we have processes and do we have gaps in those processes, and do people know the processes?” said Lazar. “Those were the two key things."

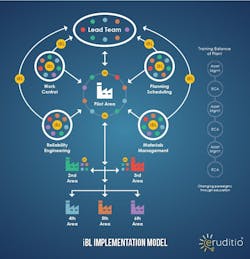

Lazar partnered with Eruditio to help design their 10-year WCM program and help identify missing process elements at Gallo. Eruditio used a combination of their iBL blended learning process and their iBL Implementation Model to create a custom plan for developing the business processes, training the key leaders, and rolling the processes out across the five sites.

One area where the Gallo team struggled was corrective work orders. “We were stuck trying to get corrective work orders into the system and into the process, so we are now measuring all of our corrective notifications” across five phases: approval, planning, identifying critical work orders, scheduling, and execution. This improvement effort also has changed the role of the planner at Gallo completely, said Lazar. “We thought we were planning; we were scheduling. Trying to get every planner to truly create a plan for the job was a challenge, but we're making progress.”

Lazar also noted that a process maturity assessment developed early in the program is ongoing four years in. “When we started this journey, there were a lot of gaps in our processes. So we do an assessment every quarter for every site, where we look at the entire system from an FMEA all the way to the execution. Was a job plan written with a notification? Was it a quality notification? We're using that assessment for more of an education for the team versus really hammering it.”

Four years into the program and across the five sites, the Gallo team has improved percent corrective maintenance from 21% to 29%, and schedule compliance from 50% to 77%. The team has made even bigger strides when it comes to logging labor and parts usage in their CMMS, which is fundamental to helping the team forecast work, understand spend, and avoid cost over-runs.

The case of the missing cycle chemistry analyzers

Tampa Electric Company stretches across 2,000 square miles of territory in west-central Florida servicing over 800,000 customers. It is comprised of a mix of coal burning units, combined cycle units consisting of natural gas-powered combustion turbine generators and steam-powered turbine generators, and twenty-one solar sites.

Shelley Penny, CMRP, RMIC, and program manager for asset management at Tampa Electric, knew there was a problem with their maintenance approach. “I was really excited about establishing programs and procedures to help protect our assets, but we were stuck in this place where there are big, giant steps to take and a lot of blanks in between. We are sitting at A and we see Z down the road and it's beautiful, but what is B-C-D-E-F? How do we get there?”

Penny and her team began measuring the reliability and availability of power producing units all the way down to the system and equipment level. “Reliability teams were formed to identify best maintenance practices across major assets and develop maintenance programs,” said Penny. “Last year, as the Cycle Chemistry Reliability Team Lead, I was asked to assist one of our stations with improving availability of their online cycle chemistry analyzers.”

The goal was to improve availability of the analyzers by strengthening the maintenance program with an emphasis on reducing the mean time to repair (MTTR) and increasing mean time between failures (MTBF), and to improve in-house maintenance enough that she could discontinue a $106,000 maintenance services contract for the analyzers. “One of the first things I wanted to do is pull the analyzer data from our CMMS,” said Penny, “and the assets weren't there! We had no parts, no work plan, no PM scheduled – then it started to make sense why the analyzers weren't functioning.”

As part of Penny’s iBL project she began to build all of the missing elements from the asset hierarchy, through FMEAs to equipment maintenance plans and PM tasks, with a project coach there to review the work and provide feedback every step of the way. “Hierarchy is really that first step,” said Shon Isenhour, founder at Eruditio. “This was one of those first things that had to happen, because data is a key enabler for the rest of the process. Almost everything we're going to do after it ties back to the hierarchy. Getting the hierarchy standardized and then building it out for the assets and equipment is critical.”

After nine months of focused efforts and following a software FMECA process, the system has gone from 11% to 65% of the analyzers fully functioning properly. “Once we were able to wrap our head around really defining those smaller steps, we were then finally able to start making progress” on preventative and predictive maintenance rather than reactive, said Penny. “It was that a-ha moment about building a plan that included the methodology to get us there.”

Historic national lab faces triple threat to smooth operations

Established in 1943, Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) does more than aid in the design and production of nuclear weapons. Today it also studies how nuclear capabilities can be applied to benefit medical research, manufacturing R&D, and advancing renewable energy.

At the Leading Reliability conference, LANL asset management operations program manager Rafael Nerell described the lab’s reliability challenge as filling in some known missing pieces. The four critical reliability challenges identified by Nerell’s team over the past 18 months include:

- LANSCE proton accelerator – an outdated computer maintenance management system (CMMS) developed more than 30 years ago for the LANL proton accelerator was still in use

- SIGMA division – no formalized maintenance and asset management program for the LANL SIGMA division, which provides metallurgical research solutions that optimize the laboratories' capabilities in manufacturing science

- MAGLAB – identified the need for an asset management program that would optimize their current maintenance processes thus meeting the National Science Foundation’s goals and objectives

- DARHT team – no formal materials management system in place, preventing this team from developing and implementing a work control process for their instruments and assets, including two large x-ray machines.

The good news is that with the support of Eruditio’s iBL, Nerell and his team are making progress on all fronts while maintaining a work life balance. “Without a clear plan the task of implementing across multiple labs would be daunting. The iBL curriculum works great to meet students where they are,” said Isenhour, “and allows them to create a proactive and reliable culture that is conducive to work life balance as well as institutional success.”

The LANL team measured their progress in several ways:

- LANSCE proton accelerator – after a six-month CMMS and asset hierarchy implementation project, a planner/scheduler has created the first work orders for the proton accelerator and they have progressed on from there. The LANSCE accelerator is one of the few accelerators in the world with an active Asset Management Implementation.

- SIGMA division – completed hierarchy for the top 25% most critical assets, identifying 5% that were mission critical, and then uploaded hierarchies into the CMMS. As it stands, more than 800 work orders have been generated, allowing for the organization to effectively track performance on their assets.

- MAGLAB – currently developing an asset hierarchy that will feed the CMMS system and trigger data generation, resulting in asset history and improved availability.

- DARHT team reorganized and centralized the parts warehouse, and approaching completion of first hierarchy for the Axis 1 part of the accelerator.

According to Nerell, the common thread that linked these projects is changing a long-standing work culture at LANL from reactive to more proactive. “The workforce is changing at the laboratory as we speak. We're getting a lot of people coming in and saying, things have to change, we cannot be so reactive all the time,” said Nerell.

In particular, the SIGMA division has been able to achieve a state where the materials management, reliability engineering, and work order management pieces are all being executed in parallel. This coordinated effort has enabled the SIGMA team to increase their planned work from 160 work orders the previous year to more than 800 this year, and the team has put together more than 100 new job plans.

“Now we can start doing recommendations and being smart with our preventive maintenance planning, and start transferring over to being more predictive,” said Nerell. “It's a very constant traction.”

Lessons learned while starting reliability from scratch

The most original presentation at Leading Reliability 2024 was delivered by Tommy Qualls and Brandon Lewis of McKee Foods. Having begun their reliability journey from scratch five years ago – no puzzle pieces, no picture, and no box – they used their conference presentation as a therapy session, one interviewing the other complete with psychiatrists’ couch and note pad.

“McKee had a very reactive culture, firefighting daily, all of that good stuff,” said Qualls. “Five-six years ago we made a decision that we were going to try to move toward that proactive realm of maintenance. We had virtually none of the processes that we're going to talk about today.”

Highlights from their therapy session included:

- Building a reliability program without additional headcount – “It was a very stressful situation, but we wound up making some of the hard calls,” said Qualls. “We decided, hey, we believe in this stuff so much that we'll pull some techs off the floor to fill positions that we have on this org chart and we will prove that it's important.”

- Implementing precision maintenance – “When we sent out job plans with precision methods in them, the techs didn’t understand why it's important to do things in a precision way,” said Qualls. “It took us a while to get that across to the crews, and for them to really buy into it. They’re slowly coming around, but we're still not there yet.”

- Implementing predictive maintenance – “We did not establish a PdM program and push out a bunch of remote sensors and say, ‘let us know when an asset is going bad.’ We really built it from the ground up,” emphasized Lewis. “We took headcount from the crews, we knew what everyone was going to be responsible for, what they were going to be required to do, and we got all of our PdM techs level one certified within the first year”

- Changing the expectations of leadership – “We didn't realize up front the skill set that our current supervision had. They got to where they were at because they lived in that reactive culture and they were really good at it,” observed Qualls. “We had to step back and start thinking, did we ever really train them? Did we ever really teach them what reliability is? Did we ever teach them how leading was going to be different in a proactive realm?”

Through a combination of traditional consulting, iBL Blended Learning, and face to face education from Eruditio, Qualls and Lewis were able to begin the long process of educating and then changing the culture at McKee. “This hybrid approach drove ownership of maintenance improvement and allowed for the development of site leaders,” added Isenhour. “They are truly champions now, able to identify and fill in the missing pieces of their reliability program, and are continuously improving performance and long term viability for both facilities.”