Taiichi Ohno, the father of the Toyota Production System, stated that all we are trying to do is to reduce the time it takes from receipt of order to receipt of cash by reducing as much waste and non-value-added activity from the process as we can. This is what is commonly referred to as lean.

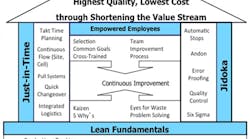

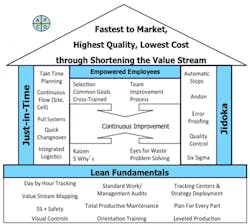

Most production systems are based on Toyota’s system. Many systems will be developed around a house in which, at the roof level, there are the overriding principles by which they operate — things such as customer satisfaction, best in class, lowest cost, and quickest to market, to name just a few. Holding up the roof are those items that drive improvement in the system — just in time, continuous improvement, cellular production, jidoka (quality built in), pull systems, and eyes for waste. And holding up the pillars is a good foundation consisting of standard work, total productive maintenance, 5S, and visual controls (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Standard work, total productive maintenance, 5S, and visual controls are a good foundation for holding up the pillars of a production system.

Almost every company has something similar. What I find most interesting is that when I am in a company and ask them what their wastes are, the majority of the time the answer to this question is a blank stare. After a few minutes, they may be able to come up with one or two of them, but it’s seldom that they can come up with all of them. So, before continuing, if you’ve identified a certain number of wastes that you look for in your organization, list them now. To help you, I’ve provided a few acronyms that I use to jog my memory. Some companies, such as Toyota, have identified seven wastes — transportation, overproduction, motion, defect, waiting, inventory, and processing (TOMDWIP). For eight wastes, which seems to be the standard these days, the common acronym is DOWNTIME — defects, overproduction, waiting, non-utilized/underutilized talent, transportation, inventory, motion, and excess processing. And some companies identify as many as 10 wastes — complexity, labor, overproduction, space, energy, defects, materials, idle materials, time, and transportation (CLOSEDMITT). So, pick one and write down the wastes that you have identified in your company.

Why is being able to identify the waste so important? To have the ability to “reduce the time it takes from receipt of order to receipt of cash by reducing as much waste and non-value-added activity from the process as we can” we must know them and look for them every time we’re watching the process or just walking in the environment, whether it is the manufacturing floor, the maintenance workshop, or the office.

The power of observation

One of my favorite stories about Taiichi Ohno was how he would draw a box on the floor and have the person that he was instructing stand in the box, not talk to the operators, and watch the process, and then report what was observed. The lesson behind this is that in order to see the true condition you need to be where the action is happening, not sitting in the office, unless that is where the action is happening, and you need to be able to watch and see the wastes. How can you see the wastes if you don’t know what they are?

I tried this exercise one time. I had an engineer who worked for me go out to the floor and observe the assembly of an electrical panel. I knew that this particular electrical panel, from beginning to end, would take about four hours to assemble. So I instructed him to come in the next morning and watch the process. I even went so far as to say, “Just observe. Don’t talk to the operators. Just observe.” In retrospect, I must not have put enough emphasis on the “just observe” part, because the next morning when I arrived he was sitting at his desk. I knew he could not have observed the entire process yet, so I asked him how it went. He said that it went great — he arrived in the morning and watched as the operator set up for the day. He explained to the operator that he would be watching the process so that he could understand how the process progressed. The operator informed him that it would take about four hours to assemble this particular assembly and he could just tell him what he did. This took about 30 minutes and he was back at his desk. What he did not see was all the wastes that occurred during the process in order to build this particular electrical panel — things such as looking for tools and materials, traveling across the plant in order to retrieve needed items, or going into the other workstations to get tools that were “borrowed” during the night shift.

Before we go on to the wastes, let’s review value-added vs. non-value-added activities. I’ve heard several definitions of what is value-added vs. non-value-added, but the one that I like most is: “value-added activities are those that the customer is willing to pay for and will normally change the form, fit, or function of the product.” This isn’t always easy to ascertain. So, is inspection a value-added or non-value-added activity? I would say that it is a non-value-added activity, because as a consumer I would hope that the processes are in place to produce a quality product. Inspection is something that the company does in order to prevent bad product from getting to the customer. This could be one of those non-value-added tasks that is necessary for the business, but it is still a non-value-added task. All of the wastes that we are about to review fall into the non-value-added category.

On to the wastes

These aren’t the only wastes that are out there, and they are meant to help you see and generate thought. If you observe something that you feel the customer is not willing to pay for and you cannot specifically fit it into a particular category, it does not mean that it is not a waste. These are also not separate entities; an identified waste can fit into multiple categories.

Let’s use the eight DOWNTIME wastes.

Defects: anything that doesn’t meet the quality criteria of a product. Defects are a direct cost and can directly affect the bottom line. Just because you do not scrap something does not mean that it does not incur additional cost. Think about it, a product gets produced with a defect, but the defect can be corrected. Do you stop at that point and correct the defect, which affects the cycle time and can hold up other products, or do you set it aside and rework it later, which will potentially create a shortage, increase inventory, and increase handling?

Overproduction: producing more than is required by the customer. This also contributes to the waste of inventory. Overproduction means you are spending time producing something that is not wanted. This creates the necessity for storage space, extra handling, and potential for defects. When I was with an aerospace company, one of the first things they did was to set me loose in a material control area (warehouse) and find a part that was older than I was. It only took a few minutes. I just looked for the part that had the most dust on it. Sometimes overproduction is necessary; factors like long setup times and poor quality will create situations for overproduction.

Waiting: I can rattle off numerous instances where I have been in a environment and seen people waiting. They could be waiting on maintenance or materials or inspection or logistics or confirmation to proceed. Toyota had the option to charge the supplier for downtime that was caused by them because, for every minute they were down they had to pay all of the team members to stand around, but they did not get the revenue of a vehicle that came off the end of the line.

Non-utilized talent: This tends to be the eighth waste that was added to the seven that Toyota identified. The people who perform the processes are usually the best ones to suggest how to improve the process. With repetition, people will automatically gravitate toward the easiest way to accomplish something. By tapping into this knowledge base, you will really start to gain exponential improvements in the process.

Transportation: can be internal or external. Internally it could be moving a part from one area of the factory to another because product flow was not a consideration when the processes were set up. Externally, if the plant that supplied you with a particular product was next to you rather than in another country, you would not have all those transportation costs. Many companies are trying to source product from low-cost countries. This adds huge costs to transportation and inventory through filling of the pipeline. When sourcing from a low-cost country, I always encourage companies to develop a total cost of ownership number, and not just a purchase price number. This total cost of ownership will take inventory and transportation into account, along with storage of parts and potential quality problems that could occur from long transportation pipelines.

Inventory: What is the value of inventory? Some companies will say it’s only the time value of money, which these days is only about 1%. But there are so many other factors that go into the cost of inventory, such as the storage cost for warehouses, handling costs, and quality defects due to handling damage. I’ve never been into a warehouse where I haven’t noticed holes in the sides of boxes where the forks just missed the opening of the pallet. I refer to inventory as exposure. If something were to happen, such as demand ceasing or a safety recall, this is the exposure that you have for lost dollars. Many people will say that inventory is necessary. I agree. A certain amount of inventory is necessary to maintain stability. Having the right amount and then striving to continuously improve is what it’s all about.

Motion: I’ve never been a proponent of kitting. It just creates additional handling, and every time you touch a part it adds cost to it. However, I was working with an automotive manufacturer and they had such an incredible variety of front headlights that to present them to the line would have taken an enormous amount of space, thus requiring the operator to have lots of motion in order to retrieve the correct part. Needless to say I’ve adjusted my view of kitting. Motion can be looked at in many ways. How much movement is occurring outside the value-added task? Do you have to turn around to retrieve a part? Do you have to walk to a storeroom to get a part? Do you have to walk to an inspection station to measure a part? All these tasks take time and do not produce a product.

Extra processing: anything that is beyond what the customer is willing to pay for. At a machining facility we were producing components to +/- 5 microns. We could have done +/- 3 microns, but the cost to do that would have been exceptional. I observed a purchasing process in which 12 signatures were required, and the PO would be placed in the inbox awaiting another signature. This signature process would take weeks — definitely an example of extra processing.

| Kimo Oberloh is a lean manufacturing subject matter expert at Life Cycle Engineering. Contact him at [email protected]. |

Defining and looking for wastes is a systems approach that needs to encompass the entire organization. Even though what is described here is geared toward the manufacturing environment, any process can be described in terms of lead time and waste. What is the lead time to get a capital request approved and what are the wastes involved? What is the lead time to process a patient and what are the wastes? All of these wastes are fairly easy to see when you understand them and look for them. But if you walk quickly through the environment without seeing, or do not know what to look for, they will continue to cost you money. So next time you are in the plant or office or field, stop and observe and see if you can identify the eight wastes that are probably happening right before your eyes. You have just never seen them in the proper light.